Uganda sits on one of Africa’s richest deposits of critical minerals—lithium, cobalt, nickel, rare earth elements, copper, and graphite—valued in the tens of billions of dollars and essential to the global clean energy transition.[1][2][3] Yet as foreign investors circle and Western governments offer technical partnerships, a deeper question emerges: does Africa, and Uganda specifically, need Black America to unlock its potential, or does the continent’s liberation depend on ending external dependency altogether? The answer lies not in a binary choice, but in understanding how diaspora contributions, Pan-African consciousness movements, and homegrown liberation structures have historically shaped—and continue to shape—Uganda’s educational sovereignty and resource control.

Uganda’s mineral wealth: sovereignty or extraction redux?

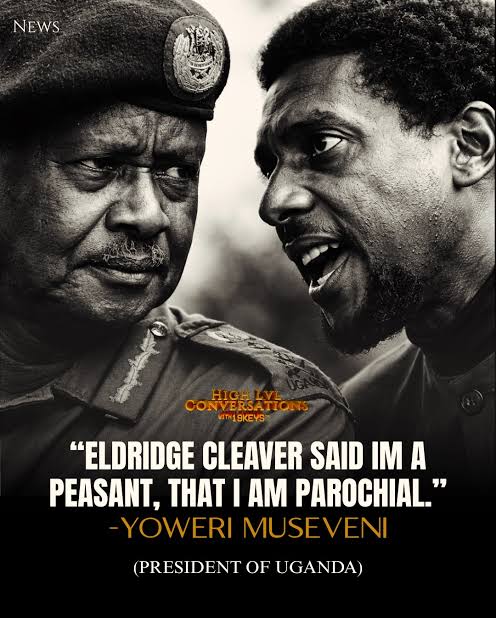

Uganda holds over 50 commercially viable minerals, including some of the world’s most sought-after resources for electric vehicle batteries, wind turbines, solar panels, and renewable energy storage systems.[2][3][4] The government launched the Uganda National Mining Company in mid-2025 to centralize control and attract investment, with President Yoweri Museveni positioning the nation as a critical player in the global supply chain for clean energy technologies.[2][5]

Lithium deposits alone, recoverable even from produced water in oil and gas extraction, could generate new revenue streams and reduce import dependence.[4] Cobalt, nickel, and rare earth elements amplify Uganda’s strategic value, especially as global copper shortages loom by 2035.[4] But history warns that resource wealth without processing capacity and educational infrastructure often reproduces colonial extraction under new management.[6]

This is where the role of Black American intellectual, financial, and organizational capital becomes contested terrain.

Diaspora contributions: remittances, knowledge transfer, and the 53 billion dollar question

African diaspora engagement extends far beyond the 95 billion dollars in annual remittances flowing into the continent.[7][8] African professionals abroad—engineers, scientists, educators, doctors, and economists—contribute knowledge transfer, strategic planning, and infrastructure co-investment that shapes local industries.[7][9]

In Uganda specifically, diaspora-led models have funded educational infrastructure, supported STEM labs, digital skills training, and entrepreneurship incubators tied to national development priorities.[8] With diaspora savings estimated at 53 billion dollars annually, African governments are increasingly designing diaspora bonds and public-private partnerships to channel this capital into schools, energy projects, and regional connectivity.[7][8][10]

Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam and Ghana’s “Year of Return” campaign demonstrate how diaspora capital can co-finance sovereignty projects.[7] Rwanda’s ICT growth, driven by Rwandan professionals abroad, shows how knowledge transfer accelerates sector transformation.[7] For Uganda, the question is whether Black American capital and expertise can be mobilized on similar terms—or whether it arrives wrapped in Western institutional frameworks that replicate dependency.

Nation of Islam in Uganda: the Islamic University and institutional legacy

The Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) decided in 1974 to establish Islamic universities across the Global South, including one in Uganda to serve English-speaking African nations.[11] The Islamic University in Uganda (IUIU), launched in 1988 with 80 students and two degree programs, now serves 7,000 students from 21 countries and has graduated over 13,000 alumni who occupy senior roles in government, parliament, the military, and civil society.[11][12]

One Ugandan minister, over 20 members of parliament, and the commander of the Ugandan air force are IUIU graduates.[11] The university’s six faculties—Islamic studies and Arabic, education, arts and social sciences, management, science, and law—operate with 30 percent Christian enrollment, signaling its role as a national institution rather than a sectarian enclave.[11] Before IUIU, even Muslim secondary schools relied on Christian teachers; today, IUIU graduates staff Uganda’s Islamic schools and export educators to neighboring countries.[11]

While IUIU is an OIC project rather than a direct Nation of Islam (NOI) initiative, the broader Pan-Islamic educational infrastructure it represents aligns with the NOI’s historical emphasis on institution-building, economic self-sufficiency, and education as liberation.[11] The university’s social impact—producing public servants, military leaders, and educators who shape policy—demonstrates how alternative educational systems can challenge colonial legacies and create pathways to sovereignty.

Five Percent Nation: pedagogy, street academies, and knowledge systems

The Five Percent Nation, also known as the Nation of Gods and Earths, emerged in 1964 when Clarence 13X (formerly Clarence Smith) left the Nation of Islam to develop an educational movement centered on self-knowledge, empowerment, and the belief that Black people are the original people of the planet.[13][14] The movement’s curriculum—Supreme Mathematics, Supreme Alphabet, and the 120 Lessons—functions as a parallel knowledge system designed to counteract the epistemic violence of Western education.[15][16][17][13][14]

In 1969, with support from New York Mayor John Lindsay and the Urban League, the Five Percent Nation opened the first “Street Academy” at 2122 7th Avenue in Harlem, providing not only education but vocational training and a sense of purpose to youth failed by traditional schooling.[13] Research shows that the Five Percent pedagogy addresses systemic gaps in serving at-risk Black youth, with nonformal education significantly enhancing academic success where traditional systems fail.[15]

While Five Percent activity is concentrated in the United States, its pedagogical model—decentralized, teacher-student networks focused on self-education and personal mastery—has influenced Pan-African consciousness movements globally.[18][15][17] The movement’s emphasis on knowledge as power, combined with its critique of Western epistemology, resonates with African liberation education frameworks that reject colonial curricula in favor of culturally grounded, decolonized knowledge systems.[15][16]

Camarilla Mask™: Liberian indigenous knowledge and cultural transmission

Camarilla Mask™ is a cultural organization rooted in the 16 Tribes® of Liberia, preserving and transmitting indigenous knowledge through traditional mask practices, spiritual teachings, and ancestral lessons.[19][20] Each mask represents specific tribal lessons, African proverbs, and spiritual messages from ancestral spirits, functioning as a knowledge archive and pedagogical tool.[20]

The organization’s work includes documenting traditional building techniques—such as cutting, bundling, and roofing cultural spaces—practiced for centuries and still alive in Liberian communities today.[19] This knowledge transmission operates outside formal education systems, relying instead on intergenerational mentorship, ritual, and embodied practice.[19][20]

While Camarilla Mask™ is Liberian rather than Ugandan, its model offers a Pan-African parallel to debates about education and sovereignty: indigenous knowledge systems, when preserved and practiced, provide alternatives to Western curricula and external expertise.[19][20] The question for Uganda is whether similar systems—embedded in its 50-plus ethnic groups—can be revitalized to complement or replace dependency on diaspora or foreign educational models.

African liberation groups and education: the Ugandan case

Uganda’s educational evolution has been shaped by civil society, missionary groups, liberation-era reforms, and post-independence struggles over access and quality.[21] In the 1960s and 1970s, missionary organizations partnered with the government to expand schools in rural areas, while elite institutions like King’s College Budo and St Mary’s Kisubi became centers of socialization, networking, and political power for future leaders.[22][21]

During the 1980s and 1990s, when political instability and conflict disrupted education, civil society organizations provided alternative learning, supported displaced students, and protected schools during violence.[21] In the 2000s, these groups advocated for Universal Primary Education (UPE) and Universal Secondary Education (USE), contributed to teacher training, and supported curriculum reform and technology integration.[23][21]

Organizations like Teach For Uganda now place fellows in low-income and hard-to-reach schools, addressing teacher-student ratios, digital access, financial literacy, and climate leadership.[21] This grassroots, community-led approach reflects liberation pedagogy principles: education as a tool for transformation rather than reproduction of colonial hierarchies.[21][24]

Uganda’s colonial education system, despite its oppressive origins, created “cultural spaces” and “new identities” that leaders leveraged to challenge British authority and prepare for independence.[22][24] Elite schools became political arenas where students learned to compete, mobilize, and build patronage networks—skills they used to seize power at independence.[22] This history suggests that education, even when imposed, can be repurposed for liberation if controlled by local actors with clear political agendas.[22][24]

Does Africa need Black America—or African liberation from all external dependency?

The tension is not whether Black America has contributed to African development—it has, through remittances, knowledge transfer, institution-building (like IUIU), and Pan-African consciousness movements (like the Five Percent and NOI).[7][9][11][8] The question is whether these contributions enable African sovereignty or subtly extend dependency by tying educational, financial, and ideological infrastructure to external actors, however well-meaning.

Uganda’s mineral wealth will be managed either by Ugandans educated in systems they control, or by foreign-trained elites beholden to Western or diaspora agendas.[1][2][3][5] The difference depends on whether Uganda invests diaspora capital into educational sovereignty—training engineers, geologists, and policymakers in locally controlled institutions—or uses it to replicate Western university models that produce graduates suited to multinational corporations rather than national development.[7][8][21]

Indigenous knowledge systems like Camarilla Mask™, liberation pedagogy like the Five Percent’s street academies, and Pan-Islamic institution-building like IUIU all point toward a third way: education as cultural autonomy, where knowledge production is rooted in African and diasporic epistemologies rather than Western frameworks.[11][15][19][13][20] This approach does not reject diaspora engagement; it demands that engagement occur on African terms, with Africans controlling institutions, curricula, and outcomes.[7][9][21]

The real question is not whether Africa needs Black America, but whether Black America is willing to fund, staff, and support African-led educational systems without demanding ideological, financial, or political control in return.[7][8][10] If the answer is yes, diaspora contributions become liberation tools; if no, they remain another form of benevolent extraction, dressed in Pan-African language but serving external interests.[9][21]

Leave a Reply